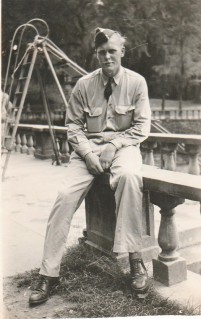

Flight Lieutenant J W Atkinson DFC

Joseph William Atkinson volunteered for aircrew duties in September 1940. In the following he takes up his story in his own words.

Sept. l940

Volunteered for RAF Aircrew duties at the Recruiting Centre, Wesley Hall, Middlesbrough. After a medical examination. I was accepted for ground duties only (as a wireless operator) because I was found to be short-sighted. Meanwhile I was sent home to await my actual call-up.

October

Received instructions to report to RAF Padgate. There I was given my RAF Service Number and was attested. I was now 1125589 AC2 Atkinson J.W. I was again sent home to await my final call-up.

Dec 30th 1940

having received my final call-up instructions and travel warrant I reported asrequired to the Receiving Centre at Blackpool. There I was kitted out, received inoculations and vaccination, and was introduced to drill, including rifle drill. This was mostly carried out in Stanley Park and on the Promenade on the sea front. The RAF had taken over just about the whole of the holiday accommodation in Blackpool and I was billeted in a series of pre-war holiday boarding houses whilst there. Unfortunately, instead of moving on to Morse Code instruction after two or three weeks as expected it was twice that time before I started because the RAF Orderly Room staff managed to lose my records. It was only after I bad made many enquiries that they came to light. In the meantime, I had another Aircrew Medical Examination, and, on this occasion, I was accepted for Pilot training, subject to my having to wear flying goggles with special corrected lenses.

Spring 1941.

Posted to RAF Aston Down (near Stroud) for Initial Training Wing Course. This was not the usual ITW course. In my case it was combined with Airfield Defence. When I was not in lectures etc. I and the others on the course were manning machine gun posts around the ing 194airfield. This meant the Course lasted twice the normal period for Initial Training. The actual course consisted mainly of instruction in Navigation, Meteorology, signals Morse c Code etc.) and theory of flight. One good thing resulting from the extra length of the course was that I was able to play a few games for the station cricket team. Incidentally, I was now a Leading Aircraftman (LAC), - aircrew under training.

August 1941.

After completion of the above I was posted to the RAF Reception Centre at Lord’s Cricket Ground, London to await posting to EFTS – Elementary flying training School — another long wait in my case because my special goggles took over three months to be supplied. Fortunately, I was given leave during this period of waiting. Ultimately my posting to EFTS came through and it was to RAF Scone, near Perth, where l had to report on the 30th December.

Dec 30th 1941.

Arrived in Perth and was billeted in a requisitioned mansion on the banks of the River Tay. We travelled to and from Scone by RAF transport. Finally, I was introduced to the Tiger Moth aircraft I was to be taught to fly, and to my Instructor, F/O Savage, who had been a pilot in the RFC/RAF during the Great War. The weather was pretty severe at times and on occasions we had to clear away some heavy snowfalls so that the flying could go ahead. However, there were also some beautiful, clear days and I was allowed to go “solo’ after about eight hours dual instruction with F/O Savage. I had made a start! Then, some weeks later, after more flying and ground instruction, the Course was surprisingly posted RAF Brough. This time we were on the banks of the Humber, near Hull, at another EFTS where we were apparently expected to stat the flying training again, from scratch. It seems to be a typical administrative botch.

March/April 1941

Flying training restarted at Brough but not a lot has stayed in the memory, apart from flying over the Humber. I remember it being quite impressive from the air. Unfortunately, I went down with a particularly severe cold (as I thought), a legacy maybe of the snow clearing days at Scone when I and all the others never seemed to be dry from one day to another. I was ill enough to be admitted to sick quarters where I was diagnosed as suffering from bronchial pneumonia. I was not fit again for two or three weeks. It was not particularly disastrous for the flying training in any case as, after some sick leave or as it turned out pre-embarkation leave, I was again posted, with the rest of the Course to RAF Heaton Park, Manchester. This was sometime in May 1942, and after a week or so there we were all on our way by train to Greenock (or Gourock, I can’t remember which) on the Clyde.

May 1942

Boarded the SS Letitia (about 18000 tons I think) and crossed the Atlantic in convoy escorted by one or two ancient American destroyers leased to Britain by America in return for some British territory (I think Bermuda comes to mind). We were bound for Halifax, Nova Scotia and docked there some ten or twelve days later. Fortunately, we were not bothered by the submarines which were loose in the Atlantic at the time the main problem for many being seasickness, with the galley too close for comfort. We slept in hammocks, which were taken down during the day and slung again at night. Altogether we were glad from all points of view to get to Halifax. There we were put on a train for Moncton, New Brunswick, a large Reception Centre for the RAF and RCAF. We were now part of an aircrew training scheme arranged with the USA, the Arnold Scheme, and in due course we were on our way to the next stage in our journey — a journey by train through Canada and south through America and lasting three days, two nights in sleeping accommodation on the train. Our final destination for this part of our travels turned out to be Albany, Georgia.

June/July

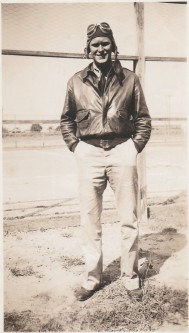

Our home for the next three weeks or so was Turner Field, a US Army Air Force Base, so that we would be able to get used to the change of climate (it was very hot and humid, being semi-tropical) and I suppose the food. This was in abundance and, bearing in mind we had come from rationing in Britain, took a while to get used to. There were lectures on health. American customs and different meanings given to similar words so that we did not drop any ‘clangers’. We were, unfortunately, introduced to Calisthenics, which seemed to be the American version of PT. One good thing, however, saw us put away our heavy RAF uniforms, which were replaced by the American Air Force issue, much lighter in weight. Our boots were also put away, these being replaced by soft and supple leather shoes. These I brought home with me when it was finally time to come back to this country. I had them dyed when I was finally demobilised and wore them for some considerable time afterwards. I have never had such comfortable footwear since.

Our time there coincided with Independence Day July 4th when there were various celebrations in Albany including a parade of the local American Armed Forces, and our Course representing the RAF. We had quite a lot of spare time much of which we spent at Radium Springs. This was a large outdoor natural Swimming Pool, the water being spring water (hence. the name of the place) and icy cold. Just the thing when the temperature here at the height of summer was in the nineties, and the humidity very high and energy sapping. But this was the' Deep South' and so we were also able to see the terrible poverty in which the black people lived. This was a real “eye-opener” some seventy years after the Civil War. They were very much second-class citizens.

August/September

At the end of July or beginning of August we were on the move again, to Souther Field, Americus, Georgia. This was a Flying Training School run by Civilian operators with civilian flying instructors on behalf of the USAAF. There was a RAF Liaison Officer on the Station for administration and discipline problems. Nevertheless we were back to square one starting from scratch once again The course was scheduled to Last about two months but this time we were to train on the Stearman PTI 7, a biplane like the Tiger Moth, but with a more powerful engine. My Instructor was a quiet Southerner called Mr. Mackie who had lots of flying hours in his logbook and was very patient. This time I was allowed to go solo after about 8 hours if my memory serves me correctly. More 'dual' followed, being shown now to look for landing fields in the event of a 'forced landing then carrying out a landing in all but touch down. 'Spins' and 'Stalls' were taught and how to recover from them, with little elementary aerobatics such as 'looping the loop'. There was a little bit of “cross country” flying thrown in for good measure. Altogether I found my time at Souther Field to be the best part of all the flying training I had had to that time. After two months or thereabouts the course was finished and we went on for Basic Training to Cochran Field, Macon, Georgia. There were some who didn't ‘make it' and were sent on elsewhere for training in different aircrew categories, usually to Canada.

October/November

Basic Training at Macron, and now we were an American Air Force Training Station, subject also to full USAAF discipline. As before there were one or two RAF Administration Personnel plus RAF Flying Instructors who had been on previous Courses and had been chosen to stay on after graduating to train as flying instructors. One of these was Michael Rennie, a well-known but minor film actor just before the war. He became much better known afterwards- and apart-from films played in many television productions.

The aircraft here was the Vultee Valiant, a low-winged monoplane with Pratt & Whitney engines and known as the BT13a. This had a sliding canopy unlike the open cockpits of the Stearman and the Tiger Moth. The instruction was an extension of what had gone before, 'dual' with both instructor and also on occasions with fellow pupils, and night flying including a cross-country with an instructor. I was also allowed to go ‘solo' to practice night circuits and landings. If I remember correctly, I had been allowed to fly 'solo' during daytime instruction after about six hours or so. On November 22nd however, Thanksgiving Day, the war and training were 'put on hold' at around mid-day All activity on the airfield seemed to come to a halt.

We trainees were paraded to the mess hall for lunch where we had the usual Thanksgiving meal of turkey, with all the usual trimmings plus one or two extras such as sweet potatoes. Each of us, whether we were smokers or not, was given a carton of American cigarettes containing ten packets of twenty and the rest of the day was free, a holiday for Thanksgiving. Next day it was back to the war. Towards the end of the Course we were asked to state a preference for the next stage of the training, the Advanced Training Course, single-engine aircraft or twin-engine (leading to four-engine). I chose single-engine but when we were moved on to Moody Field, Valdosta, Georgia early in December at the end of Basic Training it was to find it was to twin-engine aircraft. So much for preferences.

Dec/Jan '43

Moody Field was also a USAAF Station with Army Airforce flying instructors. We trainees were now a mixture of RAF and Americans, as I should have said was the case at Cochran Field for Basic Training. At both Cochran and Moody, we also received ground instruction in various subjects including Signals, Meteorology, Navigation.

The aircraft which we flew here was Boeing Beechcraft IV, twin-engined as I have said, the engines being, I believe, 280 HP Lycoming engines. I was not at all comfortable at this stage of the training, finding the two engines not at all my 'cup of tea'. We had a break at Christmas and some of us went back to Americus to have Christmas Dinner with friendly American families who had entertained us when we were there for the Primary training. Then it was back trying to come to terms, so far as I was concerned, with my two engined problems. The same situation applied to Jock Sloan, who later became my best man ten months later, and Charlie Booth who was a County Durham lad from, I think, Low Pittington, if my memory serves me correctly. Anyway, we were finally taken off the Course and had to go back to Canada. We were now well into January 1943. Whilst waiting for travel instructions we were given a few days leave which Charlie and I decided to spend in New York, although I had little in the way of spare cash, and he didn't have much more. For Servicemen however many things were free on application to the various Service Organisations. We stayed cheaply in accommodation provided this way and received tickets for shows at Radio City Music Hall, the Music Box Theatre etc. We were able to visit the studios of NBC Radio and were fortunate enough to see Leopold Stokowski rehearsing the NBC Symphony Orchestra. We also went to the Stage Door Canteen. This was a little later the subject of a typical Hollywood film. When we were there, we heard one or two of the top American Dance Bands of the day. By this time the money was really running out, but we had the nerve to try one of the bars in the Waldorf Astoria Hotel. It so happened there was a very un-market Charity Function taking place so that we could see all the moneyed Americans arriving in all their finery. Quite a sight. Next day or so it was very much back to reality for us, back to Moody Field and the prospect of another long trip, to the frozen wastes of Canada.

Feb/March 1943

We finally received our instructions to report to a RCAF Station, a huge transit camp, at Trenton, Ontario. it was, of course, the middle of winter and the temperatures were very low indeed with lots of snow, deep drifts and when it rained instead of the snow the rain froze on contact with telephone wires and the like and formed icicles. We were to remain here for a few weeks pending posting to a Navigation Course, doing nothing much that I can recall in the meantime. Finally, the posting came and it was to No.7 AOS (Air Observers School) at Portage la Prairie, Manitoba about 50 miles west of Winnipeg. We were a mixed course of RAF like ourselves, and RCAF personnel mostly newly joined. The journey to Portage took over two days, much of the time travelling along the north shore of Lake Superior. It seemed as though the Lake would never end, but we duly arrived in Winnipeg and went on to the airfield by RCAF Transport. The airfield was run by the RCAF but the flying was done by civilian pilots, the aircraft being Avro Ansons. this type aircraft had been used quite a lot in the early days of the war by Coastal Command but were now mostly used as training aircraft.

April/Sept 1943

Portage itself was a small mid-west township consisting of a main street, with a few houses, one or two shops and, of course, a bar and liquor store. When we had enough time off (48-hour pass) we more often than not spent it in Winnipeg.

The weather was perfect for most of the time and there was no interruption in the flying part of the training though one day early in Mav we woke to see some six inches of snow had fallen during the night. By midday it had gone. One of my main recollections was the heat on first getting into the aircraft and the smell of aircraft dope on the fabric of the fuselage. It was here, later in the month, that I received a telegram from home advising me that my brother Geoffrey had died. He was almost 15 yrs. old and had been ill with kidney trouble for some time. Nowadays no doubt he could have been successfully treated. Being so far away there was no question of compassionate leave. Things just had to go on.

Excellent visibility both day and night helped the navigating. We were introduced to using the sextant — sun shots by day and star shots at night —with varying degrees of accuracy. By and large though determining our position was done visually. Later, because sextant use required steady level flying many of us ruled it out as an operational tool. Night fighters made it too dangerous. The main navigation aid, Gee (a radar aid) we were to be introduced to months later at OTU (Operational Training Unit). One aid at Portage could always be relied on. There was no black-out in Canada so that Winnipeg could be seen, lit up, for many miles around. There was ground instruction also this consisting of theory and elements of navigation, with some armament’s instruction, meteorology, and aircraft recognition in addition. Most of us on the Course, which finished in early September, were successful and actually received the Observer Brevet (O), replaced by the Navigator Brevet (N) when we returned to the UK. The Brevet was presented at a Graduation Ceremony on the airfield. when we also received our Sergeants Stripes. A few days later some of us, including Jock and Charlie, were told we had been granted commissions, as Pilot Officers. There was just time to organize a Graduation Party which was held in Winnipeg. After a day or two back in Portage we were on our travels again back to Moncton.

We new Pilot Officers were given an advance on our clothing allowance which enabled us to buy our first officers' uniform before sailing back to the UK. On the way back to Moncton one or two of us stopped off in Montreal for a short visit. Then in due course we started the next leg of the journey home, travelling to New York. Here we embarked on the original Queen Mary with something like another 18000 soldiers, sailors, and airmen -- mostly American and British. Being commissioned we were fortunate insofar as we shared a third-class cabin (designed for two) with nine or ten others. The non-commissioned people were not so lucky, and many slept on deck for preference.

The voyage home was uneventful. The Queen Mary sailed without escort because Of her speed. She was diverted on one occasion — apparently, the rumour went, U- boats were thought to be around, and we were slightly delayed in arriving at Greenock, anchoring well offshore. We were taken ashore by tender, put on a waiting train, and sent on our way – to Harrogate. There we were billeted in a Hotel overlooking the Stray. A week or so later we were sent on 14 days leave. It was now late October. Two years before when I was on leave from London Mildred and I became engaged and when I was in America at Turner Field she was conscripted into the Women’s Army, the ATS. Following several moves around England and Scotland she was posted to a Unit in Lincoln. She obtained leave after mv return- In the meantime our respective parents were busy making arrangements for our wedding and we were married on the 30th October at St. Barnabas Church, Middlesbrough, where, incidentally, I had been baptized as a baby. I had arranged for Jock Sloan to be best man, but on the day he hadn’t been in touch up to a couple of hours of the actual time of the wedding. Panic stations! Fortunately, he arrived with about an hour to spare and casually proceeded to have a shave whilst everyone around was 'in a state. Nevertheless, all turned out well in the end, and there was still a week of leave to go.

Back to Harrogate and about mid-November I was posted to RAF Halfpenny Green. This was an airfield mid-way between Wolverhampton and Stourbridge.

It was No.3 (O) Advanced Flying Unit, and the first stage of the final preparations for operational flying. The Course here was termed the Air Observers Advanced

Navigation Course. It lasted a little over two months, consisting of day and night cross-country flights — mainly around the Midlands — as well as the usual ground subjects. Both night and day flying

were very different from the flying in the Canadian mid-west, where the visibility was near

perfect and at night time Winnipeg and other towns were lit up like Blackpool illuminations. It was difficult to get lost. In Britain we had to cope with a blacked-out country at night, and

balloon-barrages over the big towns. It was also wintertime so that bad weather was also frequently a problem, there was also the high ground to contend with as opposed to the flat ground of the

prairies in Manitoba. There was some additional help, however, in this country from occulting beacons. These were in fixed positions and flashed a coded letter signal in Morse. This changed daily.

When the visibility allowed it, these were good for fixing position, as were the pundits. These were red flashing lights, also in Morse, and were on the various airfields around this country. The

Course was completed towards the end of January 1943 and I was classed, having passed, as a ‘capable navigator’.

February 1944

The next stage of training was Operational Training Unit (OTU) and I was posted to RAF Market Harborough, in Leicestershire. I had only been there a day and hadn't even been given a billet when I was called to the Adjutant's Office and told I had to collect a travel warrant and report to No.16 OTU at RAF Upper Heyford. My early RAF jinx had struck again, this time it was definitely on my side. Upper Heyford was a peacetime RAF Station with permanent buildings as opposed to Nissen Hut accommodation and still retained the batman system. We were billeted in the former Officers' Mess and were well looked after indeed. On the other hand, this was where the real business started and where the crews who were to fly on operations first came together. As I had arrived a day late, most of the earlier arrivals had already ‘crewed up’. However, there was one pilot who was still short of a navigator, having found a bomb-aimer, wireless operator, and two gunners to fly with him. This pilot, I found later, had flown fighter aircraft at the very end of the Battle of Britain having joined the weekend Auxiliary flyers before the war. He had spent a lot of the time after 1940 in Training Command. He had been awarded at some stage the AFC (Air Force Cross) and was a Squadron Leader in rank. This was Dick Pexton whose family had a farm near Driffield in East Yorkshire. I agreed to join his crew as navigator and shortly afterwards I became Flying Officer. This was normal six months after being commissioned and had nothing to do with my new pilot.

The aircraft here was the Wellington, a twin-engined bomber used from the beginning of the War and known as the 'Wimpey'. Our training for operations now got under way in earnest. both in the air and on the ground. There was parachute drill, and dinghy drill this last being carried out at a local Baths and also on the nearby Oxford Canal. In the classroom we navigators had to practice keeping a log and chart. We were given at intervals information such as might be obtained on operations. This information was to be used to fix position and to decide changes of course etc.to reach a target, and return. The most interesting part of ground instruction however was our introduction to Gee, the radar hundred miles from base. In practice, however, this aid was subject to enemy jamming and at a certain stage in the flight the signals used were lost completely to the jamming. At this stage of our training, in the Radar section where there were many Gee sets for practice, we concentrated on becoming absolutely familiar with the equipment. It proved to be a great boon operationally, despite the restrictions imposed by the jamming. The flying, some of it being carried out at the satellite airfield at Barford St. John, consisted in the early stages of circuits and landings, both solo and dual, and practice bombing on nearby bombing ranges by day and night. This was in the early days of our Wellington flying. The next, and most intensive part of the flying training, consisted of day and night cross-country flying, practice-bombing, also by day and night and fighter affiliation. This was mainly for the pilot and the gunners to enable them, in theory, to deal with fighter attacks which might be encountered on operations. My job was to keep track of our position at all times and be ready with new courses to fly as and when required. was kept pretty busy which was good training for what was ahead. Altogether we put in 80 flying hours at Upper Heyford, equally divided between day and night flying, with only one scary experience. This occurred on one of the night cross-country exercises. The weather was not too good, with lots of cloud that we could not avoid. The temperature was very low, and ice began to build up on the wings, so much so that Dick Pexton found it difficult to retain our altitude. It got so bad that at one point he instructed us to put on our parachutes and be prepared to jump — not a pleasant prospect as we were at the time over the Welsh mountains. Fortunately, conditions improved, and Dick was able to maintain height and we were all able to breathe again and continue on our way.

We finished the Course in mid-April and then waited for the next stage in the training. This was to be to a Heavy Conversion Unit (MC U). This was principally for the benefit of pilots, enabling them to convert to four-engined aircraft. In due course our posting came, to 1661 HCU at RAF Winthorpe, near Newark. Here the final member of our crew, a Flight Engineer, as needed for four-engined aircraft, joined us. It was now May 1944 and our first flight here was early in the month. Although this part of the Course was principally for the Pilot and now the Engineer, we did fly two simulated operational trips over this country at night. These were called 'Bullseyes'. I never found out why. On two or three short trips the bomb-aimer and the gunners were given some bomb-aiming and air firing practice respectively. We finished the Course here in mid-June and later in the month were posted further along the Trent to RAF Syerston, No.5 Lancaster Finishing School (LFS) where we converted to the type of Aircraft we would he flying operationally- The flying here consisted mainly of circuits and landings and general familiarisation with the Lancaster. We were only at Syerston for a week or so and were then posted to No.61 Squadron, at RAF Skellingthorpe (just outside Lincoln — Mildred was still there). Skellingthorpe was also the home of No. 50 Squadron, both Squadrons being part of No.5 Group, RAF Bomber Command.

The rest of the crew, so far anonymous apart from Dick Pexton, was as follows:

Flying Officer Frank Webster — Bomb-Aimer

Flight-Sergeant 'Taffy' Price — Wireless Operator

Flight- Sergeant Dicky Morris — Flight Engineer

Flight-sergeant JOCK Gray — Kear Gunner

Flight- Sergeant Kinally — Mid-Upper Gunner

For the life of me I cannot remember his first name or nickname. He and the other NCOs were aged about 21 or 22 years, apart from Dicky Morris who was only 18/19 and looked it. Dick Pexton was, I think, 31 at the time whilst Frank Webster was a year or two older but to me looked years older, with his greying hair. All the time we were together we got on very well and the differences in rank never intruded.

The first ten days or so on the Squadron were given to practice bombing and air/sea firing, with two-night cross-country flights thrown in (one a 'Bullseye'). Then we were ready for the real thing, or so we hoped. We did not have long to wait before our first operation.

July 18th 1944

Our first operation, a daylight operation to Caen, to bomb German positions and to support the Allied forces who were trying to break through at that point.

Ours was One of a hundred of aircraft taking part in raid. In the next seven days we carried out a further five operations, two by day and three at night — four in France, Thiverny, Courtrai, Dinges, St Cyr and our first trip to Germany, to Kiel. All went smoothly. In the meantime, one of the Flight Commanders on the Squadron was posted away, having finished his tour, and Dick Pexton took over as B Flight CO.

August 1944

This month we added another eight operations to our total. We were already almost halfway to that required to complete a tour, but things were to slow down in the not too distant future. Meanwhile this month’s operations consisted of three more daylight and five night. Chattelerault, Givors, Gilz Rijen, Bordeaux and Rollencourt. Three of the night operations were to Russelsheim (Opel Works), Darmstadt and Koningsberg. This last place was renamed Kaliningrad after capture and occupation by the Russians. The other targets were mainly in France and were flying bomb sites, railway marshalling yards. There was a lot of Bomber Command activity when we went Russelsheim and there were many aircraft shot down from operations to several other targets. We were not troubled, fortunately.

The Konigsberg trip was interesting in several ways. Originally, we were not on the Battle Order for this operation and I had arranged to meet Mildred in Lincoln. At the last minute, however, one of the aircrews withdrew on account Of sickness and Dick Pexton put us on the Order. I was in my best uniform but there was no time to change and I had to go off with my flying gear on top. There were also some frantic chart preparations etc.

I could not let Mildred know what had happened either as we were not allowed telephone calls out when operations were on.

The operation itself was also of interest as it was one of the longest, if not the longest, operations undertaken by Bomber Command up to that time. We were in the air for almost 11 hours and saw both sunset and then sunrise. Another feature was that we were routed to fly over the southern tip of Sweden, though this country was neutral throughout the war. Fortunately, there was little or no opposition over the target area. I think there must have been a great element of surprise as there was little anti-aircraft fire and no night fighters showed up. There was, however, a great number of searchlights and we were 'coned' for most of the time. Only one or two aircraft were lost on this operation by Bomber Command, but none from our squadron if recollect correctly. Another raid two days later not so lucky. Returning in the early hours of the morning Taffy Price received a radio message instructing us to divert to Lossiemouth in the north of Scotland, as our airfield and all those in that area and in fact the rest of England were fogbound. So, I had to prepare new courses from then on to take us to Lossiemouth. There we had a few hours rest and something to eat and set off for Skellingthorpe, taking in one or two of our home areas on the way to have a look at them from above. Back in Skellingthorpe I was able to contact Mildred and let her know what she had already guessed. Then our logs and charts were specially called in, by Group, or maybe Bomber Command itself, for examination — no doubt because of the special nature of the operation from the point of view of navigation, A pity because they would have been a rather interesting memento.

September was a quiet month for us as a crew, although the Squadron was pretty busy as a whole. We only flew three operations, to Brest, Le Havre and Boulogne in helping the Army to prise the Germans who were defending these bases. We had a spot of leave and did not fly anymore because of the number of trips clocked up in July/August. Our total was now 17. There was also the fact that the Squadron Commander, an Australian named Wing Commander Doubleday, was leaving having completed his 'tour’ and Dick Pexton was scheduled to take over. This he did at the end of the month so that he was now promoted Wing commander and we were the squadron commander crew. Frequent changes of Squadron Commander, unless the result of losses, were not exactly planned and so the tempo of operations slowed down quite appreciably in the future.

October 1944

Nothing out of the ordinary this month – a daylight operation to Wilhelmshaven (the target I remember was covered in 10/10s cloud) and two other daylights to Flushing to attempt to breach the dykes in support of the Army. There were two other night trips this month, one to Bremen when I flew with Squadron Leader Fadden as his navigator. He was on his second tour, was one of the Flight Commanders, and was short of a navigator, his having gone sick. The second was to Nuremberg where there had been some very heavy losses on an earlier raid in March. This time it was reasonably quiet, fortunately. I was also back with my own crew. Another feature was that we were given a new radar navigation aid to try. This was called LORAN (Long range aid to navigation), was an American development I believe, and could not be jammed (unlike GEE) as its signals were reflected from the upper atmosphere laver. GEE signals followed the earth's contours and were easily jammed with spurious signals sent by the Germans. We were only introduced to the equipment on the morning of the operation and had a ‘dummy run' in the Radar Section for about half an hour. Consequently, it was not a great help and I can't remember being asked to use it again. It needed much more time from the crews than was available. We did not fly again until the following month.

In November we only flew two operations, one a night trip to attack oil refineries at Harburg (a few miles up river from Hamburg), and a 'daylight' to Duren a German border town. This was another operation in support of the Allied armies as the town was heavily fortified and defended, and in the way of the advance. Later in the month I learned that Dad had been taken into hospital. He had been suffering from a duodenal ulcer which had perforated. At the same time, following an operation on which we did not fly, one or two of the Squadron aircraft had landed at RAF Thornaby and required spare parts to get them airborne again. Squadron Leader Fadden took the parts there in an Oxford aircraft used at Skellingthorpe for this and similar emergencies and I got permission to go with him so that I could visit Dad in hospital. Needless to say, Dad got a great surprise, as did my mother. I was able to Stay overnight and go back to Lincoln by train the following day. Our crew did not fly again on operations that month.

December 1944

By this time also we were, as a crew, close to completing our tour of operations and we flew only two trips. One night operations was recalled because of bad weather and did not count towards our total. The other was a long trip over the North Sea, a little over seven hours, to attack shipping in the Oslo Fjord. I do not think much was achieved on this occasion. An interesting visit to the Squadron took place this month. There had a hold up to the American and British land forces about this time. The germans had launched a big counter-attack and had made some fairly substantial gains. Bomber Command took a hand in bombing their positions and supply lines, which was where 61 Squadron became involved with many others in the Command. The events interested the BBC and the newspapers of course and Richard Dimbleby, who was a BBC War Correspondent with quite a few flying operations behind him, and a journalist named Duncan Webb of the Daily Express. came to us and flew on one of the operational trips. Frank Webster, our bomb aimer, flew with the crew taking Dimbleby as their bomb-aimer was unfit. Frank was 'over the moon of course to be flying with this broadcaster who was very well known even in those early years of his career. They came back without any trouble.

Duncan Webb and his crew were not so lucky. The operation was carried out at a fairly low level and they ran into some very heavy fire. The aircraft was badly damaged and, if I remember correctly, crash-landed behind the Allied lines, though some of the crew, and their passenger, were ordered to 'bale-out'. Poor Duncan Webb landed in a tree and broke a leg, with some other minor injuries as well. Adding to his discomfort he lost his flying boots on the way down at the end of his 'chute. All the others survived with no ill effects.

January 1945

Unexpectedly this turned out to be our last month with 61 Squadron. We had a long (over 91/2 hours) trip to Munich where the gunners saw one of the German jet fighters which we had heard they had in service in small numbers. Fortunately, we were not seen and we were pleased to be on our way back to Skellingthorpe. Later Dick Pexton told us that was our last trip, although our total was one or two short of the usual, and we were now 'tour- expired'. Apart from a trip to Hutton Cranswick, an airfield near to Dick Pexton's family farm, in the Oxford, and an air-test with S/L Fadden a few days later that was the last of my Squadron flying. I had flown almost 150 hours on flying operations, with over 87 hours being on night operations. The crew went on leave and returned in due course to learn where we to be posted for instructional duties, the usual thing for tour-expired aircrew. One thing we did know and that was that we would be separated and go our different ways. In fact, I never saw any of the crew again except Frank Webster, who I ran into at the Demob Centre in April 1946 quite by accident. I saw Dick Pexton a few months after 'demob' when we went to the first squadron reunion later in the year. I also saw him briefly two or three years later when he called at the office on his way to Hartlepool on the way to a wedding. Otherwise that was it. Frank and I exchanged Christmas cards for a few years, as did Dick and I, but this faded out gradually.

March 1945/April 1946

In late February, or early March, I was posted to 26 Operational Training Unit at RAF Wing, an airfield near Leighton Buzzard and Aylesbury, as a 'screen navigator', i.e. navigation instructor, both here and at the satellite airfield at Little Horwood. This was now about a year on from my time at Upper Heyford when I was a pupil on the way to a Squadron. I was to remain here until I was demobbed over a year later. I flew with the pupils coming through the course checking Gee, and his general navigation skills. At the main airfield we tended to send the crews on cross-country exercises (day and night) whilst at Little Horwood we flew with them on practice bombing trips. It was at Little Horwood that I had a rather lucky escape from a very sticky end. Two pupil crews were scheduled to fly to the local bombing range to carry out an exercise and were to be accompanied by a screen navigator. I was the only instructor available for some reason and decided I would fly with a pilot I had flown with before. We got along very well. It was a lucky choice because the other aircraft took off on the exercise without a screen navigator and over the bombing range, in cloudy conditions, collided with another aircraft and crashed. The crews of each aircraft were killed instantly. We saw the whole incident as we were still on the ground awaiting our take-off instructions. I couldn’t help but think 'what if... ? Most of my time in the air at Wing and Little Horwood was in March — April. Then, in May came VE Day (Victory in Europe). When the news came through there were great celebrations all over the country. Some of us from Wing were in Aylesbury and were able to join in the general fun and partying there. There was a huge bonfire in the market places with the usual fireworks to which some folk added their contribution or Very cartridges. The local pubs were open all day the following day so that the festivities were carried on. Local Church and similar Halls offered sleeping accommodation for those who could not or did not, wish to return to their units on VE night.

There was still the war in the Far East however still to be resolved so that the Course had to be continued, though, it must be admitted, at a slower pace. In fact, I only flew six more times at Wing, the last trip a sightseeing trip taking in Emden, Wilhelmshaven and Bremen with a few ground crew passengers to let them see the damage done by the raids on these places. Previously I had been sent on a short Radar Instruction course at RAF Feltwell where I was introducted in the use H2S a navigation aid used on many other Squadrons in Bomber Command, but not on 61. On this short Course I was introduced to the Halifax aircraft. This Course only lasted a day or two and then it was back to Wing.

There I was able to play in the Station cricket team, which was very enjoyable indeed. The Station was entered in the countrywide RAF Station Cricket Competition and we managed to get into the semi-finals before going out of the competition. Altogether Service life had become very pleasant but there was always the thought that soon my six months off operations would run out and I would have to serve a second tour over Japan, a prospect I did not fancy too much. Fortunately, for me, this did not happen because of the dropping of the atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August. At that time, I was actually in Felixstowe, a Coastal Command Station and also a pre-war permanent Station with wonderful Mess facilities, where I had gone with another player from our cricket side. He was to play for Bomber Command against a Coastal Command side, and I was there as a reserve. In the event I was not required and carried on home to Middlesbrough on leave. Whilst I was on leave in Felixstowe the Japanese surrender was announced and a lot of people on the Station went very much 'over the top in their celebrating, burning some of the Mess dining tables on the lawn in front of The Officers' Messe These were beautifully made tables and there was no real excuse for such vandalism. I was glad to get away next day to start my leave.

Later in the month Mildred was demobbed – married ATS were released first — and after a short time I was able to get lodgings for us in Leighton Buzzard. I obtained permission to live-out and this arrangement lasted until I was myself demobbed the following April. Mildred obtained a part-time post as shorthand typist with a local firm of Solicitors and all in all it was a comfortable way to wind down our war. Comfortable though it was however it couldn’t last and demob instructions caught up with me. It was then back to my civvy job with the Commercial Union, though I took the maximum amount of demobilisation leave before going back.

There were two more events to record before I left Wing. Firstly, I became Flight Lieutenant. an automatic rise in rank. This occurred after two years commissioned rank. Then, around the same period I was surprised to receive some telegrams congratulating me on being awarded the DFC for my tour with 61 Squadron. Apparently, it had appeared in the London Gazette sometime in August 1945. And it had reached the local paper in Middlesbrough. There was a small reference in one of the editions. Dick Pexton was also awarded the DFC to go with his AFC, and Frank Webster received a MID (Mentioned in Dispatches). I received the actual medal through the post some months later in the summer of 1946, with a printed communication from George VI. And that is about all there is to it — civvy street lay ahead, after nearly six years away.

We are grateful to F/Lt Atkinson's son Bryan Atkinson for the story.

Joseph William Atkinson passed away 18 February 2023.

Mike Connock