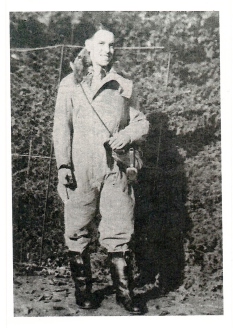

Sergeant Glyn Owens

Pilot

4 June 1915 - 7 July 1941

Glyn's Brother Rhys Owens tessls the story of his brother;

Our family lived in Porth at the junction of the Rhondda Valleys in South Wales. This was a famous coal-mining area and our father was employed as a blacksmith and ropesmith in the local Lewis Merthyr Colliery (where the Rhondda Heritage Park is now situated).

Glyndwr (usually called Glyn) was born on June 14th 1915, the eldest of three brothers (the others being Teifi and myself, Rhys). He attended Porth Secondary Grammar School and when he left there went to London to work. He worked in the office (known in those days as “the counting house”) of a large Knightsbridge store called Woollands. Lots of young Welsh people left the Valleys to seek work in English cities. It was the avowed intention of both our parents that none of their sons would have to follow their father into the mining industry. Whilst working in London Glyn joined the Metropolitan Police as a special constable. He spent many weekends directing traffic in the West End.

By 1938 Glyn had moved to Oxford and was managing an antique shop. In July 1936 the government had announced a plan for the formation of the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. It came into being in 1937. Volunteers were to be recruited for a minimum of five years. Trainee pilots were expected to have had grammar school education, or education of a good standard. They were to receive a retaining fee of £25 a year and appropriate allowances while under training. Flying training would be at weekends and during an annual fifteen day camp.

In the 1930’s, private flying was very much a rich person’s sport, so the opportunity to learn to fly, and to be paid while doing it seemed, to many young men, an opportunity too great to miss. Glyn was accepted into the RAFVR as a trainee pilot and like all trainee pilots was given the immediate rank of Sergeant. His service number was 754046.

His flying log book shows his very first flight was in a Miles Magister on 25th June 1939. Between then and 27th August, he received dual instruction from RAF and civilian instructors.

As the threat of war neared, Glyn was called up for full time service on 1st September 1939. He came home to Porth with all his flying kit prior to posting, but on the evening of 3rd September police called at our home with a recall for Glyn to report back to Oxford immediately. It was too late to catch a train so the police took Glyn down to the main road below our house. In a short while they flagged down a lorry which (believe it or not!) was going to London, via Oxford.

No 22 Flying Training School (Marshall’s, Cambridge)

20th December 1939:

Started receiving instruction on flying Tiger Moth aircraft.

11th January 1940:

Flew first solo on Tiger Moth.

By 24th May Glyn had flown solo in Tiger Moths for 60 hours 40 minutes (day) and 35 minutes (night).

No 15 Intermediate Training Squadron

Posted to Middle Wallop to learn to fly twin-engined aircraft.

28th May 1940:

Commenced training on Airspeed Oxfords.

5th June 1940:

First solo in Airspeed Oxford.

After three weeks at Middle Wallop the course was transferred to South Cerney. (The nearby village was later to become the home of Teifi – our brother - and his wife Freda). The hangars and control tower are still on the old airfield but the site is now occupied by the Army).

During his time there he flew down to Porth. One morning a bright yellow (the colours used for training aircraft) Airspeed Oxford came down the valley low over our town. A letter from Glyn a few days later confirmed that he had been the pilot. This was his second flight over Porth – his previous flight was in either a Miles Magister or Tiger Moth. Henceforth, the folks in Llwyncelyn blamed any low flying aircraft on Glyn!

Advanced Training Squadron, Chipping Norton

Training continued on Airspeed Oxfords. It was here that Glyn gained his coveted ‘Wings,’ to signal that he was a qualified pilot. (For a fuller and amusing account of how they had been trained and how the men heard of their award of their ‘Wings,’ read Charles Lockyer story. This follows on after the end of Glyn’s story).

At the end of this course Glyn was categorised as “above average on Airspeed Oxfords.”

School of Air Navigation, St Athan

This base was only about twenty miles from Porth so almost every evening four Sergeant Pilots arrived at our home, 34 Leslie Terrace (I was the envy of every boy in the street). Alan Somerville, Angus Riley, Charles Lockyer and Glyn, who were great friends. All four were newly qualified pilots but only one – Alan Somerville – could drive a car. He owned a small Standard 9. If they were not on night flying duties they immediately jumped in the car and headed for Porth. Food was strictly rationed but somehow they were fed by our mother. Then off they went to a dance at the hall of our local St Luke’s Church. I should imagine that four young, good looking RAF pilots were very welcome visitors.

It was at these dances Glyn met Eirwen Thomas of Nyth Brân. They became very close and Glyn regretted very much at the end of his last leave that he had not asked Eirwen to become engaged to him. Eirwen was to suffer a double tragedy in the middle of 1941: on 8th July Glyn was posted missing and on 28th August her only brother, Sgt. Evan John Thomas RAFVR was killed in a flying accident at Bicester. His body was returned to his family for burial in Trealan Cemetery.

At St Athan they all flew in Avro Ansons learning advanced navigation by day and night. They flew as navigators, often flying out over the Irish Sea. The course was pretty intensive, as well as attending ground lectures, Glyn flew 23 hours, 5 minutes as second pilot/navigator between 10th September and 1st October. By 5th October the course was completed.

No 14 Operational Training Unit

The four close friends were posted to No 14 Operational Training Unit at Cottesmore in Rutland. All their kit was crammed into Alan Somerville’s Standard 9 and they set off on their drive to the new posting.

27th October 1940:

On Glyn’s second day of flying at Cottesmore he went on his first solo in an Avro Anson.

27th November 1940:

Taken up on a familiarisation flight in a Hampden (1 hour) “No RAF Hampdens were fitted with dual control and pupil pilots could only become familiar with the take-off and landing procedures by sitting on the wing-span behind the instructor pilot and watching what happened. After several such flights the pupil would be cleared to make his first solo, followed by several hours of circuits and bumps.” (Page 178 ‘The Hampden File’ by Harry Moyle).

That same day, after his first flight in a Hampden, Glyn did his first night flying solo in an Anson.

29th November 1940:

- Taken up to test for solo on a Hampden.

- First solo on a Hampden doing circuits and landings.

(Only his third trip on this type of aircraft).

Many exercises followed: one engine flying, climbing and gliding turns, cross country flights, W.T Training, instrument cross-country flights, high and low level bombing practice, camera bombing.

10th February 1941:

Glyn practised solo dusk and dark landings. “The pilot’s introduction to night flying invariably took place at dusk, being preceded by a couple of landings as the daylight faded, then continuing into early darkness.” (Page 178 ‘The Hampden File’).

25th February 1941:

Categorised: Medium Bomber Pilot – Average: Pilot/Navigator – Above Average.

At Cottesmore he seemed to have been known to his comrades by the nickname of ‘Baron.’ A letter from Gordon Harvey written from RAF Cottesmore to our family (dated 10th July 1941) confirms this.

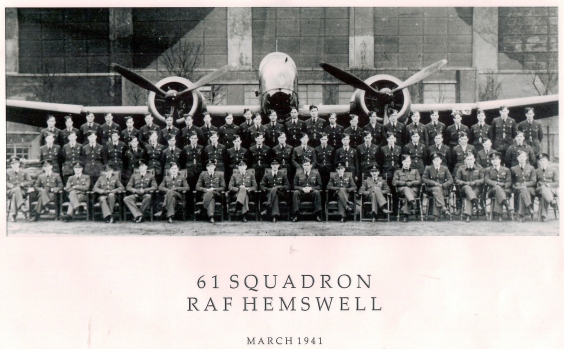

61 Squadron, Hemswell (5 Group)

In March 1941 Glyn was posted to RAF Hemswell, north of Lincoln.

After one solo flight in a 61 Squadron Hampden and a short night flight as navigator, Glyn was detailed for his first operational flight.

Usually newly joined pilots did several missions as navigators before captaining their own aircraft. It was policy to fly two pilots in a Hampden, one acting as the navigator/bomb aimer. As time went on, this was considered wasteful and the policy was changed.

15th March – a/c AD825:

Bombing raid on Dusselforf. Pilot: Sgt Metcalf, Navigator: Glyn, Air Gunners/W.Ops: Sgts Copeland and Lodington (killed 8/9th August 1941 in a raid on Kiel - Roll of Honour 61 Squadron). 6 hours 10 minutes spent in the air.

Two aircraft from 61 Squadron and six from 14 Squadron (also stationed at Hemswell) took part in this attack. There was fog but bomb bursts were observed. Both of 61 Squadron landed at Tangmere and flew back to base next day. No reason for this is given in the Squadron Operations Book.

20th March a/c AD825:

Minelaying off Brest. Pilot: Sgt Stevenson, Navigator: Glyn, 2 Air Gunners/W.Ops Sgt Randall (killed 7th December 1941 in raid on Boulogne – Roll of Honour, 61 Squadron) and Sgt Smith. 6 hours spent in the air. One or two fires observed.

30th March a/c AD826:

Operation against Brest. Crew: as on raids of 15th and 18th. “Requirement for the attack was 7/10 over Brest. The aircraft went out in echelon formation, stepped down. Thirty miles over the English Channel the aircraft were ordered to return owing to complete lack of cloud cover over Brest. Three aircraft from 61 Squadron and three from 11 Squadron returned to Hemswell (61 Squadron Operations Record Book). Obviously cloudy conditions were necessary to prevent the German defences observing accurately where the mines were being dropped.

31st March:

Flew to St Eval. Same aircraft and crew as on 30th March. Operation against Brest, but again adverse weather intervened. Landed at Tangmere; could not return to Hemswell until 3rd April.

7th April:

Bombing raid on Kiel. Same aircraft and crew as on 15th and 18th March. 5 hours and 40 minutes spent in the air. Perfect weather conditions. Six Hampdens of 61 Squadron successfully located and bombed the target area. Heavy A.A. fire and several enemy aircraft seen. All Squadron aircraft returned safely.

21st April:

Flew as second pilot on air test of Avro Manchester (This type was coming into squadron use – 61 Squadron had received its first one in March – but the type proved underpowered and had problems with the tail design: after a short operational life, they were withdrawn).

In the middle of June Glyn came home on leave but before his leave ended he was recalled by telegram to proceed to Cottesmore on a captain’s course. He, in fact, returned to Hemswell, probably to pick up his kit, belongings, etc.

7th July:

Flew as navigator on night raid on station and marshalling yards at Munchen Gladback.

A/C AD937:

Pilot: P/O J.G.N. Braithwaite, Navigator: Glyn, W.O./A.O. J Walton, A.G. F.Sgt. R. Wordsworth. (Extract from log-book of F.Sgt. L Boot, W.O./A.G. on AD 826 – “Take-off 22.45 hrs. Hot trip. Down to 1200 ft. Forced to gun searchlights. Braithwaite’s crew – Blondie Wordsworth, Joe Walton and Glyn Owens missing”)

“Good weather conditions aided the attack on Munchen Gladback railway station, but only one aircraft attacked the station, others attacked the town. Successful photographs obtained. One aircraft attacked by Me.110 and was damaged. Jettisoned its bombs. The Me.110 was seen spinning earthwards. One aircraft with navigator injured crash landed at Coningsby. Forty Hampdens took part, two failed to return.” (61 Squadron Operations Record Book).

On the return flight from the target AD937 was attacked and shot down by Lieutenant Reinhold Knacke in his Me-110. Burning, the Hampden crashed in a meadow near the village of Houthern in the South of Holland. The pilot bailed out and survived, he was captured by the Germans.

Pilot Officer Braithwaite in his prisoner of war debriefing report (dated 3rd May 1945, File W/344/38/1 at the National Archives) wrote that he sustained ‘extensive burns’ on the night 7/8 July 1941. He received some treatment immediately he was captured and then no further treatment for four days. He was 20 years of age when he became a prisoner. His service number was 87058, his POW number 9973. He was kept in Stalag Luft III.

The bodies of the three members of the crew who had not survived were collected by the Recovery Group from the German night fighter base at Venlo and interred in a cemetery, which had been established by the Germans in the grounds of the St. Joseph Hospital, along the Dokter Blumenkampstraat in Venlo. When the war was over it proved impossible to keep the cemetery at that spot for practical purposes; it was next to the buildings of the hospital which needed to be extended. The airmen of the Commonwealth were subsequently re-interred in Jonkerbos War Cemetery, Nijmegen. Glyn’s grave is plot 20, Row G, Grave 5. The simple Welsh quotation on his headstone is “Hyd doriad y wawr,” which in English means “until the day breaks...” this is a quotation from the Bible; it is found in The Song of Solomon, Chapter 2, Verse 17. The start of the verse reads, “until the day breaks and the shadows fly away......” The choice of inscription was made by our father, John Owens.

Pilot Officer Braithwaite in his prisoner of war debriefing report (dated 3rd May 1945, File W/344/38/1 at the National Archives) wrote that he sustained ‘extensive burns’ on the night 7/8 July 1941. He received some treatment immediately he was captured and then no further treatment for four days. He was 20 years of age when he became a prisoner. His service number was 87058, his POW number 9973. He was kept in Stalag Luft III.

Glynn Owens in the cockpit. P/O Braithwaite on the left. The man in front is Sergeant Len Boot. Len Boot was on Hampden AD826 on the same raid when AD937 was lost. His log book reads; "Take of at 22.45. Hot trip. Down to 1200ft. Forced to gun searchlights. Braithwaites crew, Blondie Wordsworth, Joe Walton, Glyn Owens missing".

The bodies of the three members of the crew who had not survived were collected by the Recovery Group from the German night fighter base at Venlo and interred in a cemetery, which had been established by the Germans in the grounds of the St. Joseph Hospital, along the Dokter Blumenkampstraat in Venlo. When the war was over it proved impossible to keep the cemetery at that spot for practical purposes; it was next to the buildings of the hospital which needed to be extended. The airmen of the Commonwealth were subsequently re-interred in Jonkerbos War Cemetery, Nijmegen. Glyn’s grave is plot 20, Row G, Grave 5. The simple Welsh quotation on his headstone is “Hyd doriad y wawr,” which in English means “until the day breaks...” this is a quotation from the Bible; it is found in The Song of Solomon, Chapter 2, Verse 17. The start of the verse reads, “until the day breaks and the shadows fly away......” The choice of inscription was made by our father, John Owens.

Glyn was the first of seven boys from Leslie Terrace to be killed during the war; six were RAF aircrew and one was a soldier who died in the Battle of Normandy.

At about midday on Tuesday, 8th July 1941, Mr and Mrs John Owens of 34 Leslie Terrace, Porth, received a telegram from the Air Ministry informing them that their son, Sgt. Pilot Glyn Owens, had failed to return from operations over enemy territory the previous night.

Having slept some hours the night before, our mother woke our father and said she had heard a loud explosion. They both feared there had been a severe accident in the local colliery. Our father opened the bedroom window and enquired of a passer-by about the explosion, only to be told that no explosion had occurred and that it was a peaceful night. When the telegram arrived at midday, our mother knew instinctively in her heart that Glyn had been killed. Dad tried to stay more positive saying that he could be a prisoner of war, but Mam knew differently.

Over twelve months later the Air Ministry informed the family that Glyn was “missing presumed killed.” Later again, they were informed by the International Red Cross that Glyn had been killed and was buried “somewhere in Holland.”

Glyn’s Uncle, Mr Tal Davies, lived in Newlyn, Cornwall. He was a gifted but amateur masseur. Just after the war ended he was asked to give some treatment to the skipper of a Dutch salvage-tug stationed off Newlyn. Mr Davies refused any payment for the treatment but asked the Dutchman if he could perhaps help to trace where in Holland his sister’s son was buried. Not many weeks after, a letter arrived at Mr and Mrs Owens’ home from a young Dutch lady, Mrs Jo Versteeg Van Lin in Venlo, South East Holland stating that she was caring for Glyn’s grave in Venlo and inviting our family to go to the home of her parents (Mr and Mrs Van Lin, Herungerweg 120, Venlo) if they wished to visit the grave. It was months later before the Air Ministry was able to confirm Glyn’s burial place.

In July 1947 Mr and Mrs Owens and I (Teifi was not able to go) travelled via London, Harwich, Hook of Holland to Amsterdam. We initially caught the wrong train at the Hook, so arrived in Amsterdam later than expected. As we walked up the platform of Central Station a loudspeaker announcement came that we would be met at the bottom of the stairway. Jo had sent us her photograph beforehand and stated that she would be wearing an orange flower. We recognised her and were introduced to Kees, her husband.

Mr and Mrs Owens stayed overnight in the flat of Kees’s mother and I stayed with Jo and Kees with Kees’s sister. Next morning we went to Central Station to catch a train to Venlo.

The family were warmly welcomed at the home of Mr and Mrs Van Lin. Mr Van Lin worked for Phillips, the large electrical company and spoke good English, as did Jo and Kees. Mrs Van Lin was a kind lady who spent most of her time in a wheel-chair; she spoke little English, yet managed somehow to convey her warm and genuine feelings to her visitors.

The first visit to the cemetery was a very emotional one. The graves of the British and Commonwealth airmen were a blaze of colour and were lovingly cared for and respected by the local people. Wherever the Owens family went and whoever they met there was so much gratitude from the people. The Dutch people had just suffered four years of foreign occupation; husbands and sons had been taken for forced labour – some never to be seen again. Thousands of Dutch people – including Kees’s first wife and child – had died of starvation or disease. Yet these very people were overwhelming in their gratitude for the sacrifice made by Glyn and his comrades. Jo’s constantly repeated phrase, “We owe you....” and is still being used by her daughter, Annemike, who was not even born when the war occurred.

As Glyn was initially buried in Venlo it was always believed by his family that his aircraft had come down near this particular town. After Mr and Mrs Owens had died this assumption was perpetuated by the two remaining brothers, Teifi and I (Rhys), both of whom had followed their brother into the RAF, Teifi also became aircrew, made a career in the service and retired as a Group Captain in 1977. I did National Service as a meteorologist in the RAF before taking up teaching and retired in 1989.

However, in 1990 the belief that the aircraft had crashed near Venlo was shown to be incorrect. Harry Moyle, an ex Hampden crew member, published ‘The Hampden File.’ In it he listed what happened to every Hampden bomber that was ever built, 1430 in all, and where appropriate, the names of the crews and their fate. The book, a meticulous piece of research revealed that Sgt Owens’ aircraft, serial no AD937, returning from a raid on Munchen Gladbach was shot down at Houthem, near Meerssen in S.E. Holland. This is not far from the town of Valkenburg. It was shot down at 01.17 hours by Oberleutnant Knacke of INJ91 Squadron.

I decided to contact Harry Moyle, hoping that the author could provide more detailed information with regard to the crash site. Harry Moyle was unable to assist but suggested that I contact Mr John Hey, a Dutchman, who is a member of a voluntary organisation which researches the fate of all aircraft, Allied and German, which crashed in Holland in World War II. Simultaneously, Teifi and I decided to visit Holland with our wives in April 1991, the 50th anniversary of our brother’s death, to visit his grave and to enquire in the Meersen area with a view to determining the actual crash site.

This is when fate took a hand, Mrs Janice Thomas, having no knowledge whatsoever of Sgt. Glyn Owens, contacted Teifi and his wife Freda and asked if they would care to join a small party going on holiday to Holland – destination Valkenburg! Teifi and Freda had been on previous journeys organised by Mrs Thomas and agreed to go on the trip. My wife Ray and I joined the group.

On the first Saturday night in the hotel in Valkenburg, Teifi and I were contacted by two young Dutchmen: Mr Ron Putz and Mr Peter Mourmans, the latter being an N.C.O. in the Netherlands Air Force. Both were voluntary researchers into aircraft that had crashed in their area in the war. Mr John Hey had asked them to investigate the fate of Hampden AD937. Ron Putz already had recorded over three hundred aircraft which had come down in the locality, but their investigations and research contained no details of the subject aircraft; neither were they aware that it had crashed in their area.

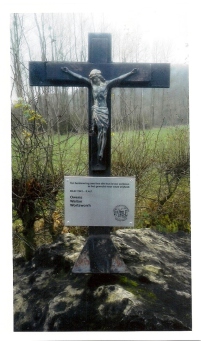

Again fate took a hand. Whereby it sometimes takes months and many interviews before the actual crash sites of individual aircraft can be pinpointed, the second person they interviewed was able to tell them exactly where the aeroplane had come down to earth. It was just a five minute journey from the hotel where the holiday party was staying. On the Monday evening Mr Putz and Mr Mourmans took Teifi, myself, Freda and Ray to the crash site and showed us the exact spot where AD937 had come down. There is a small area of the field on which the plane lay where apparently nothing has since grown.

Afterwards, the group went to a nearby hotel – Hotel Berg en Dal – Geullhem – where the daughter of the previous proprietor gave Teifi and I a piece each of the wreckage. They had been recovered from the site by her late father who had given them to her prior to his death.

Finally, Messrs Putz and Mourmans gave the brothers a photograph of Oberleutnant Knacke, who bore a resemblance to Glyn. The night fighter pilot, who was himself killed on 3rd February 1943, had been based at Venlo and a book, containing his photo, had been written about the German Air Force’s wartime operations from that base.

Teifi and I asked Ron and Pete why they gave up so much of their spare time, with no financial support, to make all these enquiries and do so much investigation and research. They replied that the aircraft and crews had made a very significant contribution to their freedom. Therefore, they believed that the sacrifice should never be allowed to be forgotten and they hoped that the date of Allied aircraft and their crews, which came down in Holland in World War II, should be recorded in perpetuity in a published book; this was their aim.

In 1994 Ron Putz published the results of his research and investigations in his book ‘Duel in De Wolken’ (Dual in the Clouds). The Owens family were able to give Ron some help in telling his story. He was completely unaware that virtually all of Holland had been photographed from the air by the RAF in the war. My and Ray’s son John had been a student at Keele University where all the reconnaissance photographs were then kept. John made contact with his old university; Teifi and I appealed to the Ministry of Defence for Ron to be allowed to use some of the aerial photographs without payment of a royalty fee. The Ministry agreed to this, provided that ownership of the copyright was acknowledged. Ron was able to include about ten aerial photos of S.E. Holland in his book. Ron gave Teifi and I each an English copy of the part of the book, which tells Glyn’s story. He dedicated it to the Owens family and its title is ‘Third Reich Without a Roof.”

Teifi and Rhys had come to realise that they had to wait for Ron and Peter to be born, grow up and take up their particular hobby before they could be provided with the details of their brother’s fate, which had occurred fifty years ago.

Teifi started a campaign in the early 1990’s to have the Porth War Memorial updated, with the names of those who had died in Word War II added. He wrote to the Rhondda Council, Royal British Legion and to the Rhondda Leader. He enlisted friends in Porth to get information. By August 1996 he had compiled a list of over one hundred names, which was published in the Rhondda Leader. However, due to the indolence of the Council and the Royal British Legion, Teifi never lived long enough to see the fulfilment of his efforts. It was not until 6th May 2007 that the new Porth War Memorial – with Glyn’s name on it, was finally dedicated.

Glyn’s name is commemorated at:

Porth War Memorial

Roll of Honour, St Luke’s Church, Porth

War Memorial, Porth Comprehensive School

5 Group Memorial Books, Lincoln Cathedral

St Clement Danes Church, London

Groesbeck Freedom Museum, Netherlands

Memorial Book, Jonkerbos Cemetery, Nijmegan

Wall of Names - International Bomber Command Centre

We are grateful to Rhys Owens for the material and photographs for this story on his brother.

Mike Connock